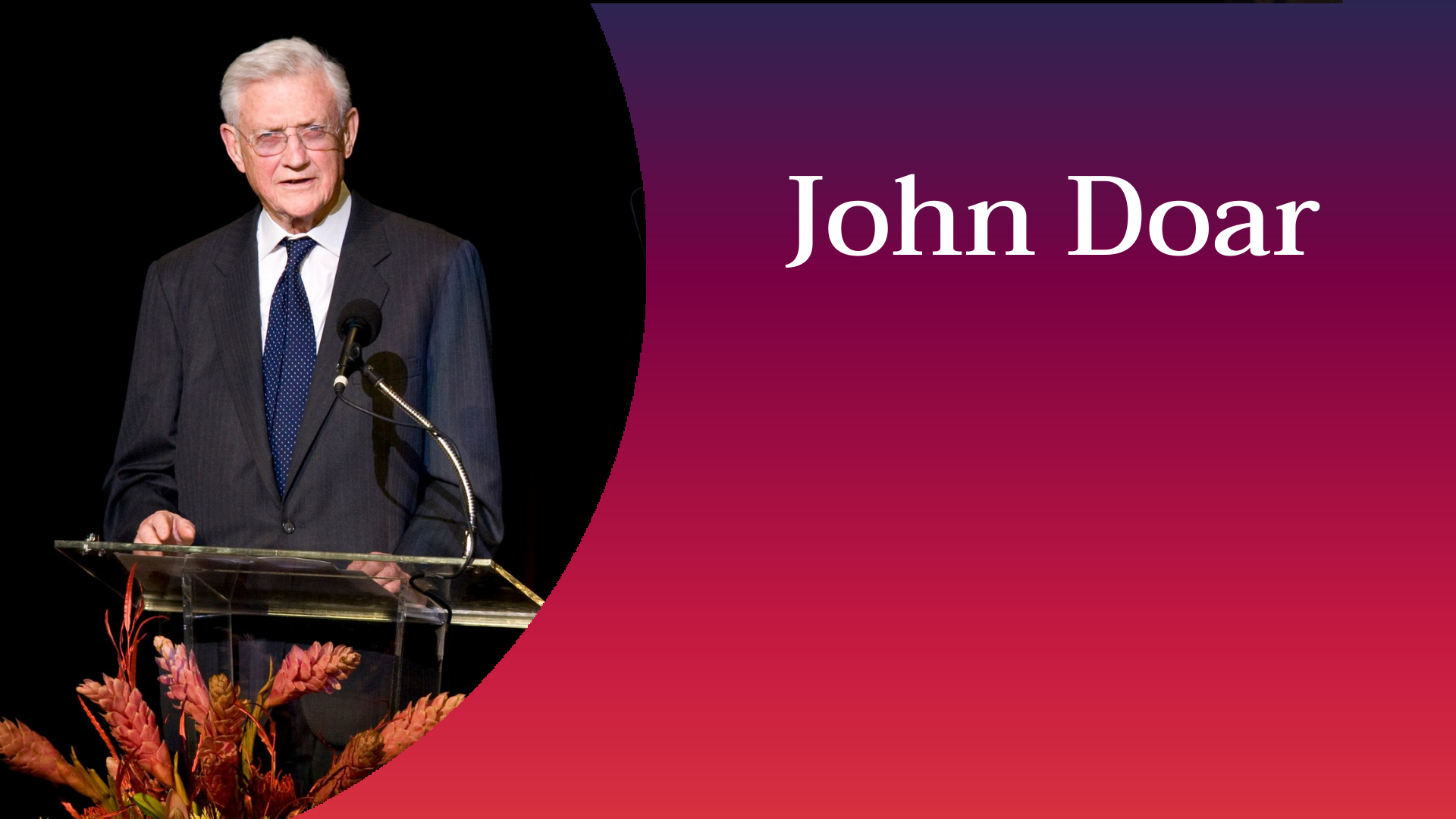

Congressman John Doar

2009 Choral Arts Humanitarian Award Recipient

Transcript from John Doar’s speech at the 21st Annual Choral Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on Sunday, January 11, 2009 at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

CONGRESSMAN JOHN LEWIS

Good evening. I am Congressman John Lewis. I am pleased and delighted to be here tonight to pay tribute to my friend and my brother, John Doar. John Doar and I played different roles while we were both participants in a nonviolent revolution that changed America forever. As faith, or something I would like to call “the spirit of history”, would have it, we both joined the struggle in the same year, 1960. I was a college student who had been inspired by the words and the action of Martin Luther King, Jr. to get in the way, to get in trouble. Good trouble, necessary trouble, nonviolent trouble. I joined other students and began sitting in and sitting down on lunch counter stools in Nashville, Tennessee, who wanted to challenge the system of legalized segregation and racial discrimination.

In those days, African Americans could buy a meal, but they could not be served with other patrons inside in a restaurant or other public accommodations throughout the South. It was against the law. Inspired by the success of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott a few years earlier and well trained in the tactics of pacifist, nonviolent resistance, groups of well dressed, peaceful protesters would sit down on lunch counter stools in segregated restaurants and wait to be served.

Someone would come along and spit on us, pour hot coffee or other drinks on us, or put a lighted cigarette out in our hair or down our backs. Sometimes we were beaten, arrested and taken to jail. These were the kinds of civil rights violations John Doar was supposed to investigate. But he was a lawyer from Wisconsin. He did not know much about the ways of the South, and he had been hired that same year in 1960 as chief deputy of the Civil Rights Division of the United States Department of Justice. He had just moved to Washington, D.C. Before he joined the department, agents were doing armchair investigations trying to determine from a distance, through a long, complicated questionnaire, whether a civil rights violation had actually occurred in these cases. These acts may seem like plain abuses to you and me, but often when local authorities would ask about these incidents, the facts were not always clear. Segregation was the law of the land in most Southern States. John Doar decided he could not discover the truth by sitting behind a desk. He decided he had to go south and see the problem for himself, and that became the genius of his work.

John Doar did not have a cell phone. He didn’t have an iPod, he didn’t have a website. He didn’t have a Blackberry. He did not have a federal police force to come to his aid, but he had himself and the power invested in him by the United States government, and he used his power to make a difference in our society. He was the first Justice Department lawyer to actually attend mass meetings in the churches in the backwoods of Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, Tennessee, or South Carolina. He would visit black citizens wherever they lived, whether it was in an old, rundown shotgun house on a farm miles away from a town or city, or a nice wooden frame house in a black section of town. He would listen to them and document their stories of segregation and racial discrimination. People told him when they attempted to try to register to vote, then they were fired from their jobs, evicted from their farms.

They might wake up in the blackness of the night to find huge crosses lit on fire and burning in their front yards. They could be taken from their homes by the night riders. Some were beaten, shot, even killed. And when he heard these stories, John Doar realized that legal segregation and racial discrimination was a peculiar institution. He understood that injustice had been written into the legal codes of states all across the South, and he decided to use his power and his expertise to get in the way. And he did get in the way.

It was dangerous, very dangerous to challenge this way of life. Many who had tried to buck the local authorities were run out of town. They had to endure death threats, bombings, even beatings. John Doar displayed nothing short of raw courage to do this work. He allowed nothing to hold him back from the cause of justice. Martin Luther King, Jr. used to say, “Sometimes you have to turn things upside down to get down right side up.” John Doar left no stone unturned. He was tall, lanky, and he stood out in a crowd. He got in the way because we trusted him and we knew he stood for a purpose, right? He could be a force for good.

After the murder of Medgar Evers, civil rights leader, field secretary for the NAACP in Mississippi, in 1963 [there was] John Doar, who was able to quiet a mass of blacks who threatened to riot in frustration. It was John Doar who brought federal charges in the murder of Viola Liuzzo, a housewife from Detroit who drove down to Alabama as a volunteer and was killed on the return from the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965. He seemed to be everywhere in those days. I remember the story told by a conversation between four reporters who were trying to get in church with him:

“John Doar’s in Birmingham,” said the first one.

“No, he’s in New Orleans,” said the second.

“Oh, I just saw him here in Jackson,” said the third.

“You all are right,” said the fourth reporter. “He was in Birmingham this morning, argued a case in New Orleans this afternoon, and arrived in Jackson this evening.” John Doar was everywhere.

It was a long, grinding effort, cases after cases, proving injustice of legalized segregation before judge after judge. Nobody knew when there was setback after setback, when injunctions were denied, when law enforcement officers continued to break the law. Nobody knew when thousands of nonviolent protesters were beaten, arrested and taken to jail. Nobody knew when John Doar risked his life in American South that just 40 years later, this nation would overcome enough to elect the first African American president of the United States of America.

John Doar was more than a lawyer, more than a federal officer. He was a representative of a higher law, a higher power, who risked his life for the cause of civil rights and social justice in America. This man, this great civil servant, represents the kind of decency and goodness that made him make this nation the most powerful nation on earth. Everyone here tonight, all of us, are indebted to the work of John Doar and other participants in the movement for fundamental change. Because of them, this nation and American people have witnessed a nonviolent revolution under the rule of law, a revolution of values, a revolution of ideas.

So it is my pleasure and my great honor to present an award tonight to John Doar on behalf of the Choral Arts Society of Washington. John, because of your raw courage, your dedication to the cause of justice, your tireless effort to challenge this nation to live up to the meaning of its creed, you and your associates at the United States Department of Justice have made a lasting contribution to the cause of civil rights and social justice in America and around the world. For honoring your oath of office, above and beyond the call of duty, for adhering to the precepts of freedom and equality that are written on the hearts of all humankind and inscribed in the Constitution of the United States, I am pleased to present to you the Choral Arts Society of Washington Humanitarian award for 2009.

JOHN DOAR

You know, it’s awfully hard to respond to an introduction like that. Perhaps I could say something that I try to be humorous with, but it doesn’t seem quite appropriate. John was really talking about bigger things and lots of people besides myself who worked under Burke Marshall in the Civil Rights Division, and he didn’t exaggerate one bit. He didn’t exaggerate one bit about the danger and the risk that John Lewis and the other students of the Non-Violent Coordinating Committee lived under day in and day out in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama in the years 1960 to 1965, at least. Bob Moses, who was a field agent for the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee in Mississippi for those years, said once that the lawyers in the Civil Rights Division under Burke Marshall gave he and his colleagues crawling space, just crawling space, and that was about all we could do, to try to do all we could to help these courageous young men and women try to break the caste system that existed throughout the South in America.

So because I feel so deeply as to what occurred and what was good for the country coming out of that experience, I agreed to accept this award tonight knowing that it was in recognition of the work of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. During the time, the division was under the leadership of Burke Marshall. Now, six months later, the decision of the Choral Arts Society to recognize and acknowledge the work of Burke Marshall and all the lawyers, paralegals and staff of the division is especially relevant in view of the election that occurred on November 4th, 2008. The recent election has affected the stature of the United States today and will affect the stature of the United States far into the future. During his second inaugural address, President Lincoln, in reporting to the nation about the progress of the war, said neither party expected for the war, the magnitude or the duration which it had already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease before the conflict should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph and a result less fundamental and astounding.

If one were to have read that speech by President Lincoln in 1960, one would have wondered just exactly what President Lincoln had in mind. True, slavery had been abolished. True, the country had grown and prospered. But fundamental and astounding, hardly. There still existed large, large numbers of black citizens in the South who weren’t even able to register or to vote. But within five years came the passage of the Voting Rights Act, and soon thereafter, November 4th, 2008. The result of what happened on November 4th, even before the polls were closed, was fundamental and astounding. As we heard report after report of the number of citizens who showed up at their polling place to cast their vote and realized that these voters included countless numbers of black citizens, we realized that finally, at long last, our country had reached its goal. It had finally established an honest system of self-government.

The time will come when the American people will think of the 4th of November just like the 4th of July, as a day of special significance in the history of this country. We are here tonight to celebrate another great American day, the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King.

Each of us has our own independent memory of actions by Dr. King that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act or contributed to its effectiveness. I have many such memories. One happened in Tallahatchie County, located in the heart of the state of Mississippi. Shortly after Burke Marshall became Assistant Attorney General in March of 1961, he assigned two young lawyers to go to Tallahatchie County to investigate the issue of discrimination in voting. They returned with a notebook full of information on that subject. And by the fall of 1961, the Justice Department was ready to file a suit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi, challenging the acts and practices of the sheriff and the registrar in Tallahatchie County. Two lawyers prepared affidavits based on their earlier interviews to Tallahatchie County to obtain the signatures of the black citizens who had the courage enough to agree to swear to what their experience had been with the sheriff and the registrar.

One of those citizens was a wonderful woman named Mrs. Kegler. She agreed to tell her story, swear to her story, so that we could use that in order to move for an injunction before the judge in the Northern district. And at that time, I remind you, that while there were over 6,000 black citizens who were registered, who were eligible to register and vote, not a single black person had ever voted in Mississippi in Tallahatchie County. Looking back, the act of Mrs. Kegler seemed so infinitely disproportionate to what had to be done to secure for all black citizens their constitutional right to vote. And so the struggle went on in Tallahatchie across all of Mississippi, across most of Louisiana and parts of Alabama, from that day until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of ’65.

During that time, I had many occasions to see examples of how Dr. King’s words or his actions moved the cause forward. But one thing, one incident that I remember – that maybe some or all of you have not heard about – was what happened after the act was passed, after the Supreme Court upheld the validity of the act, when James Meredith in 1966, the year after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, decided that he would lead a march across Mississippi for the purpose of urging black citizens to register to vote. And he wasn’t 20 miles within the borders of Mississippi, south of Memphis, before he was shot, wounded and had to be taken to the hospital in Memphis. That resulted in another freedom march by the black citizens and the black leaders, picking up the march after where Meredith fell and carrying it down through the Delta on toward Jackson, Mississippi.

One day on that march, Dr. King decided that he would take a detour and go over to Tallahatchie County, and he did that with a small group of his followers. I was there that day, and I can remember as if it was yesterday that Dr. King got out of his car, went up and stood in the center of the yard in front of the courthouse, which was in the middle of a typical southern square. And at that time there were white men and women mingling around in the street. There were no police around. There were no federal soldiers around. There was just Dr. King and his group, and the black citizens of Tallahatchie County were holding back and leaning against the fronts of the stores that surrounded the square. And then Dr. King began to speak, and the essence of his speech was that he urged everyone to step forward and come to register to vote that day. As he spoke, first one black citizen came forward, then three, then five, then eight, then a whole group of black citizens lined up in front of the courthouse door ready to go in and be registered. Dr. King told the group that he would stay there that afternoon until every single black citizen who wanted to register would get registered that day. And he did that. And over 150 black citizens registered in Tallahatchie County that day. When that was completed, Dr. King led a march down into the black section of the town, past Mrs. Kegler’s funeral home, back up and around the courthouse square. And it was a glorious march. Spirits were high. The citizens were optimistic. And as I left Tallahatchie County that night, I knew that Dr. King had broken the spirit of segregation in Tallahatchie County.

Now that was just one county in three or more states. And when Burke Marshall took office and assumed the duties of Assistant Attorney General, he decided that the way to break the caste system, the way to break second class citizenship, was to secure for all black citizens the right to vote. And I want to tell you how he did this. In the first place, you must remember that nobody in the Civil Rights Division, or really in the federal government, understood the process that went on when people registered and then were certified that they were eligible to vote. This required lawyers and paralegals and the Civil Rights Division to learn all about the individual records, not just of the three states that were principally concentrated on, but also in many, many of the counties of the states. So that we in the division, we lawyers in the division, would know every single thing about how the registration process worked.

(I used to tell the lawyers and the paralegals that there was romance in the records. I’m not sure whether they believed me or not. By the way, and absolutely with no relevance to the situation, I would like to report while I was in the Civil Rights Division, seven years, six of the lawyers married six of the paralegals. I’m proud and happy to report they’re all together to this day.)

Let me tell you how the lawyers worked at that time. John has referred to the fact that we went south, and that is true. And what we did was that on a Friday afternoon late in 1961, and thereafter for the next three years, I would come out of my office in the middle of the afternoon, I’d see suitcases and briefcases lined up outside the office doors where various lawyers worked. There were at that time 10 or 15 lawyers that were working on voting matters, and these lawyers, in pairs, would leave Washington, catch the plane to Atlanta, change to a DC-3, and fly. The first stop would be perhaps Montgomery and two lawyers would get off there, and then the plane would stop at Meridian and two lawyers would get off there, and then in Jackson, and then at Monroe, and then at Shreveport. And those lawyers stayed in the field for 16 days, going to particular counties to which they’d been assigned, asking questions, interviewing people, looking at records until they got to know those counties, four or five counties that each of the assigned lawyers had.

And this enabled Burke and the other lawyers in the division to prepare cases, and to really, by 1963, know every single thing about the registration process in those three states, and the common substance of what we knew was that these three states were operating an absolutely corrupt and dishonest system of voting. If you were a college black college graduate, in many of these tougher counties, the chances were pretty slim that you would even get a chance to register. But if you were white and if you breathed, you voted. That extent of the corruption was such that the lawyers in the division were so indignant about that, that they worked and worked and worked and prepared massive cases of factual cases demonstrating to the judges in the Fifth Circuit just exactly what was going on.

And the benefit of that was that by the end of 1963 or early in sixty-four, that the federal judges who were southerners, white southerners – five judges really, in effect – certified the accuracy of the findings that the Civil Rights Division lawyers presented to them. For example, Judge Johnson in the Middle District of Alabama established the principle that the standard for registration was measured by the qualifications of the least qualified white who voted. Now, the least qualified white who voted was a white that breathed, period. Judge John Minor Wisdom declared in a memorable opinion that there is a wall erected between the black citizen and registering to vote. Judge John Brown of Texas declared in another case that this evil is so bad that a frontal attack across the whole complex of laws and regulations and procedures and culture was warranted to eliminate the evil. And at that time, Robert Kennedy commissioned Burke Marshall to give two speeches at Columbia University with respect to the right to vote and the administration of justice. And Burke was able, in his wonderful way, to graphically paint clear pictures of exactly what was going on. And what he said in those lectures and what he communicated to the American people, and particularly to the public men and women in Washington who would be called upon to consider an enact legislation to eliminate this evil, what he said was: this system of voting in Mississippi and Alabama and Louisiana is corrupt, and that corruption is affecting our whole federal system. It’s having a corrosive effect on the kind of government that we all live under.

And then, as you remember, came Selma, Alabama. And shortly after that the new legislation, which wiped away all the educational and literate standards that had been purportedly required, the Voting Rights Act, was passed. And then 16 months later, or 15 months later, the Supreme Court upheld that statute and said that Congress had the power to give to the Attorney General any number of methods by which he could imaginatively eradicate that evil. And the Supreme Court added that hopefully, hopefully, that this would provide the fair opportunity for all black citizens to register to vote and vote.

So I come back where I started, achieving an honest system of self-government has not been easy, but now we are possessed with new energy. We have earned new respect. With our heads held high, we can now confront other difficult problems that we face. Thank you.